Lake Sailor 4m

Stock Plans Order Form / Back to Aruna 33 / Back to Design Page / On to Island Girl 24

Some friends of ours took us out to a local lake a couple of summers ago. We had a wonderful time sitting on the shore and watching the water, but we couldn't help noticing the intriguing islands scattered across the lake. We would desperately have liked to have had a sailboat with us that was small enough for a couple of people to stick in the back of a pickup or van and light enough for a couple to hoist up on top of a car. We thought immediately of a little double ender, like a beamy double paddle canoe with a little more freeboard.

All in all a pretty darn good Lake Sailor. Unfortunately the sheer molding was moved down away from the actual deck edge, which impairs the appearance a bit. For some reason the builder fitted two of the push/pull tillers and a double arm on the rudder head instead of a single tiller. I also notice that the rigging at the yards has been vastly over complicated. I have no idea why. All that's needed here is a single halyard for each sail. Apparently the sails were made out of Tyvek. Since the labor would be pretty much the same as building the nice tanbark sailcloth sails but they'd only last a season at most, there can't be any real reason to do this.

Originally I thought I'd make her about 10'6" long and about 4' wide on the bottom or 4'6" beam over all. I figured she'd have leeboards and a very low single sail Chinese rig of no more than 63 square feet. The total weight of the boat without the rig and gear would be about 60 lbs. to make her easy to carry to the water. Personally I would have a small electric drive attached to a battery and solar panel as paddling is difficult for me these days. She could be an awful lot of fun for very little money. The materials for a boat this size are pretty minimal. Have we just reinvented the canoe yawl? Perhaps, but in a very small form.

I put the above concept in the idea designs section of our web site where it attracted occasional attention. Finally a Swiss gentleman liked the concept enough to have us produce some renderings of what she would look like.

In thinking back over our acquaintance with boats of this general size range and type we came up with an additional thought. Two boat types came to mind for additional information that we could use. One was a sailing peapod. The other was best represented by an undecked sailing canoe designed by Bob Baker called the "Piccolo". In both cases these vessels were double ended and had a very slightly deeper outside keel than you would have on a pure rowing or paddling vessel. Yet in both cases they sailed well without any additional leeboards or centerboards. On this basis we decided we could do without leeboards.

In any case, compared to the original concept we ended up with a tiny bit more freeboard in the ends as the boat sits on the beach. Given the greater beam than most sailing double paddle canoes this means she will have a fair amount more freeboard for any given crew weight than we are accustomed to seeing in these boats.

We also ended up with a little more overhang both fore and aft. This is what stretches the vessel from the original 10'6" (3.2 meters) to 4 meters (13' 1-1/2"). The idea here is that you end up with more reserve buoyancy in both bow and stern. You also end up with a bow shape that tends to turn the bow wave over before it gets to the sheer and therefore keeps the boat much drier.

Even though we don't have anything like a self bailing cockpit adding a deck makes the boat much more seaworthy, or perhaps we should say, "lake worthy". The short chop that often develops in lakes tends to make a boat pretty wet but the bow shape and the deck should keep you as dry as you are ever going to manage in this size boat. Also under the deck fore and aft there is a fair amount of space that is never going to be used for any kind of gear storage. It is very easy to make some nice foam blocks to fill these unused spaces. This means that the boat will be unsinkable which is a very nice feature. She will float high enough so that if you do manage to capsize her, which will be darn hard to do if you are paying any kind of attention in most conditions, you can turn her upright, remove the mizzen mast, press the stern down enough to straddle it and then hitch yourself forward until you can swing your feet inside. Then as long as you keep your weight low you should be able to bail out and keep sailing without much problem. Given that crew weight is most of the displacement and the sail area is modest and low this capsize drill should be pretty much a theoretical possibility.

The final change from the original concept was that we made her a little narrower. She is now just a hair over 1 meter wide (3'5"). We've seen a number of sailing canoes narrower than this that seemed to perform well. One vessel that my brother sailed a bit, the "Piccolo" mentioned above is about 3/4 of a meter (2'6") wide. Although for other reasons mostly suitable for harbor sailing he felt that she was pretty reasonable in stability. I'm told that Pete Culler sailed his open canoe about this size and very narrow in quite strong winds at times. Further, keeping the beam down helps keep the weight down. Therefore on balance I think the narrower beam makes sense.

Rig

Canoe yawls of this general size range have a modest amount of wetted surface for their length. They are not very stable boats yet are very easily driven. However designers tend to put relatively enormous rigs on them. I have seen this over and over again. I suppose this is because they are thinking of lots of sail area in relation to displacement and wetted surface. However these boats want to have a small enough sail area so that crew weight is pretty likely to overpower the heeling effect of a puff, providing you aren't sailing with too much sail up anyway. If you have a hot planing day racing dinghy you want plenty of sail area in relation to weight so you can get up on a plane. However in our little Lake Sailor you are never going to plane. A decent breeze will get her up to about 4-1/3 knots. Any reasonable breeze at all will get her up to about 3-1/4 knots. In this speed range acceleration counts for very little. My choice then is a modest rig for comfortable sailing. Originally I was going to arrange this in a single Chinese low aspect ratio rig. However the design fought me tooth and nail on this. Everyway I turned she clearly was indicating that she wanted a very low aspect ratio two sail rig, so that is what she has. The main has an area of 2.3 square meters (24.8 square feet). The mizzen has an area of .725 square meters (7.8 square feet). The main is made of a minimum of .1 kilogram per square meter (3 oz. per square yard) dark soft Dacron, Terelyne or other polyester cloth. A soft cloth will be easier to handle and will last longer. A dark cloth is easier on the eyes and much more resistant to ultraviolet radiation. Therefore this is another reason that it lasts a lot longer. The mizzen is of similar cloth in a minimum of .07 kilograms per square meter (2 oz. per square yard). As in many of her sisters of this size and type the assumption is that rather than reef you will simply take down sails. She will carry the rig shown up to stronger winds than you really should be out in anyway.

I gave this rig a lead of 4.7% of the waterline length Center of Effort of the sail area over Center of Lateral Plane without the rudder. This looks right. It's in line with my past experience. However we could easily find that this is not ideal. Ideally under sail in moderate winds and with both sails trimmed about the same she should have just a very slight weather helm. The chances are moving an inch or two fore or aft one way or another will balance her no matter what. However in fine tuning the boat you can change the rake of the masts slightly, or alter the attachment of the halyards to the yards as well. In making the mast partners and mast steps I would remember that provision for a little adjustment may be a good idea. I would doubt very much whether you would ever need to do anything else but you also have plenty of room to move either or both masts without much trouble if you wanted to.

Lines

This is one of those small boats that is deceptively simple in appearance. Many little double ended vessels of this type are of highly simplified shape for ease of planking using lapstraked planks. Many also have sheers that look good on paper but are a little disappointing in three dimensions. We have worked very hard with Lake Sailor to make sure that the bow is just enough higher than the stern so that she will avoid too much bland symmetry. In plan view the deck line looks very similar fore and aft yet it really is subtly different. Most important of all, in three dimensions you can view the boat from any angle bow to stern and at any angle of heel without finding a view in which the sheer is anything other than a beautiful flowing curve. I am fortunate in that I was taught the development of sheers by a very accomplished boat builder, several master designers, and my father. We have gone on to develop our own methods based on formalizing their work and have found that we can now reliably do sheers that are very visually satisfying with much greater ease than I would have thought possible.

The sections show a hull that is fine at both ends under water but broadens out above the water for good reserve buoyancy. This would be difficult to do in lapstrake but in sheathed strip construction is quite easy. Further this lends a subtlety of shape that is rare in this small a boat and is visually quite pleasing. These ends will make the boat more seaworthy than most boats based upon the canoe model and much better at keeping water off the deck.

The midsection is very flat floored and with a fairly hard curve to the bilge. In other light canoe yawl types with carvel or lapstrake planking this shape would not be ideal for steam bent frames and would probably be compromised to keep the frames from breaking. Additional compromise would come from the need to accommodate the wider planks. It would also be common to see some deadrise at the midsection. However this more dinghy like section is best in a very small boat of this type to make boarding and moving around in the boat easier. It also produces good initial stability for the proportions. Again more deadrise is often used traditionally to make planking them easier. Fortunately this is not a worry with sheathed strip construction.

The fine ends and the small depth of full length keel will give her much more resistance to leeway than you would think possible. As near as I can tell she will never need a leeboard. If anybody wants one I'd be happy to draw one, but I doubt it will be worth the complication.

Obviously where the waterline is on this vessel is somewhat arbitrary. The waterline shown assumes two 77 kilograms (170 lb.) people about 31.75 kilograms (70 lbs.) in the boat itself and 13.6 kilograms (30lbs.) in the rig. Hopefully the final weights will come out less than this but you've got to figure people always add stuff to boats and never take anything out. Thus the total displacement as shown would be about 196 kilograms (431.75 lbs.).

If you assume one person is sailing the boat she floats a bit higher. She then has a total displacement of about 122 kilograms (270 lbs.) If people are a little heavy or they take camping gear with them, she'll float a little lower.

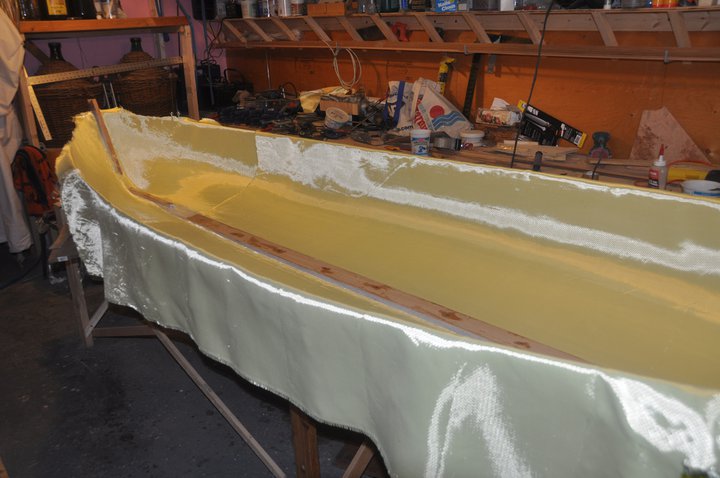

Construction

While we design in most materials and are usually pretty flexible about designing for whatever material people want, in the case of this boat it would be very hard to find a better choice than sheathed strip construction. Sheathed strip will normally be lightest for a given strength or the strongest for a given weight of any of the normal construction methods. It is also very good for use in this sort of subtly shaped hull. For those who are not familiar with the construction method it derives from strip plank construction. A century ago in Hampden, Maine someone noticed that they could plank a hull with the square section strips that formed the waste from a saw mill operation that I believe operated on Pitcher's Brook, later known as Reed's Brook which flowed into the Penobscot River. This brook flows through land that was at one time owned by my family. After World War II the master designer Cyrus Hamlin showed us all how you could take this type of square section strips and make beautiful boats of light, strong, and durable construction by edge nailing and gluing the strips together using modern glues. This worked so well that many of the earliest boats built this way and designed by Mr. Hamlin and others are still sailing today and often look brand new. In the late 1950's another wonderful designer named Lindsay Lord developed the immediate precursor of modern sheathed strip construction by sheathing the strip planking inside and out with various cloths and early forms of epoxy to eliminate frames. Some of these boats also are still sailing and still look good. In the latter 1970s your present author took this basic method and engineered the first scantlings rule for the method. This rule, along with better glass and carbon fiber for the sheathing seems to have caused sheathed strip construction to become more and more a prominent material all around the world for a wide range of sizes and types of vessels. Because it is completely non-proprietary there is no incentive for anyone to push the method yet every year more and more vessels are built this way.

In my book sheathed strip will remain one of the top contenders in construction methods at least until the far reaches of material science like carbon nanotubes become inexpensive enough to replace carbon fiber and other fibers in boat construction.

The rudder pintles ended up 13mm (1/2") in diameter. When I first worked this out this seemed significantly larger than most boats this size that I've worked with and I thought "Gee, I've always found these calculations reasonable before." Then I recalled how much time I spent when I was younger repairing the rudder fittings of small boats and came to the conclusion that my calculations were correct. The rudder fittings on most small sailboats are just too small for long life.

Rig

The rig uses two simple unstayed round tapered and solid Sitka spruce masts. Halyards may run over small sheaves if you wish but we've shown them just running through carefully carved holes in the mast.

As mentioned above, we've shown dark red cloth because it is easier on the eyes and lasts longer due to better resistance to ultraviolet rays.

This rig keeps center of effort low and makes good sail set easy. It is yet another factor in the design that tends to make this boat hard to capsize.

Auxiliary Propulsion

Lake Sailor is a little wider than a normal single paddle lake and stream canoe but you could paddle her with one or two single paddles in the fashion of Maine guides and our native American forebears.

She is a fair amount too wide for easy double paddling while sitting on the bottom in typical double paddle canoe fashion. I would recommend a conventional double paddle but I would kneel with a pad under your knees and a very low slant top seat to rest your bottom on. The boat is wide enough so that this shouldn't result in any stability problems.

Personally I'm a great double paddle canoe fan who can no longer reliably paddle because of infirmities that make it too painful. For others in this position I think I would recommend one of those flexible solar panels on the deck, hooked to a small marine 12v battery and attached to an electric drive like those that people attach to their outboards for trolling for fish. I'd fasten this to the rudder just above the waterline for low drag when sailing. When I was becalmed and needed to get somewhere I'd move a little further aft in the boat to immerse the propeller and turn on the motor. Even the tiniest of these motors would probably push you at least three knots so it will be pretty easy to get home.

Evocative

In Maine we have a vast network of lakes throughout the state. I can sure see taking her "up country" to the grand lakes just north of us. Probably I'd do this in early fall when it was cool enough and dry enough to not worry so much about black flies and mosquitoes. The whole boat and all our camping supplies would fit in the back of our van with the door open. Anywhere that looked convenient at one end of the lake system my wife and I would take the boat to the water with one of us tucking the bow under an arm and the other tucking the stern under an arm. A second trip would bring down the rig, steering gear, floor boards and paddle. A third trip would handle our gear.

While my wife took Lake Sailor out for a little explore to see if we should camp on an island, a local point, or just unroll a sleeping mat for the night in the bottom of the boat with our bow tied to a tree tucked in behind some point, I'd take the van to the other end of the lake system and hitchhike back.

When I got back I'd probably find that some little rocky point or islet had become our temporary home with a fire laid and a tent pitched. She would come pick me up, enthusing about the scene, the pictures she took and the sketches she'd make to paint from. Supper would probably be soup and homemade bread with ginger beer to drink and cocoa for desert. The quiet in our tent with Lake Sailor resting beside it would be profound, and broken only by an occasional fish jumping, or an occasional owl or loon.

When camping, morning comes early and we would be up and about with our gear packed and sandwiches made for the day. Nevertheless we won't have much wind for awhile so we just rig the boat and push out onto the mirror surface of the lake feeling we should disturb it as little as possible. Drifting with one of us leaning against one coaming and the other leaning against the opposite one we share a topographic map back and forth discussing where we should explore and how far we might get today.

For an hour or so we paddle down the lake toward some interesting looking islands. Gradually we feel a few puffs of air and see little catspaws of wind chasing across the water. Since I love really like light weather sailing we would immediately put up the sails and follow my standard pattern of steering toward the next little patch of wind and only making dramatic course changes in the wind patches.

Gradually as the morning goes on the wind will strengthen. We wouldn't be in any big hurry so if the wind got at all strong we'd just take in the mizzen and shift our weight a bit to rebalance the helm. Since we aren't pressing the boat the sailing remains relaxed and by noontime we have gone through a small archipelago and dipped in and out of some beautiful coves. With the sun high in the sky we run into a little cove, drop the sails and let her coast in until the bow just grounds on the beach. Lunch is pulled out and consumed while looking out over the lake and inspecting the topographical map looking for someplace near where this lake joins that next one that looks like a good place to stop. Several possibilities are discussed but we decide that we'll just have to look at them as we come to them. In the afternoon we are nearing a little rocky spit of land that looked like it might be a good place to stop when we see a dock and collection of small buildings on the shore in a shallow cove partially protected by an island. Deciding to duck in there and see what this establishment is we change course. An older couple comes down to the dock as we sail in. We learn that this is a camp which fishermen rent cabins at in the spring and summer. Now they are getting ready to close for the winter but offer one of their cabins for our use tonight. They are intrigued by Lake Sailor and invite us to a dinner of trout right from the lake that evening. We sit up quite late listening to stories of bear, moose, raccoons, and the strangest animal of all, the summer sportsman. In turn we describe last year's exploration of Moose Head Lake and where we plan to go from here. They pull out some notebooks with little sketches and maps of various islands and coves, with notes on the fishing and desirability for camping, which we gladly copy. They are somewhat shocked that we don't have fishing gear with us and insist on giving us some older gear left behind by long forgotten fishermen.

Late at night we retreat to the cabin they have loaned us and light a fire in the fireplace. From the bed we can see Lake Sailor resting at the dock in the moonlight and looking the other way into the room we see the fire in the fireplace. Snuggling down we think about our day and the days ahead exploring this great system of lakes.

This is one scenario and a wonderful use for Lake Sailor. This is a great way to use her for a younger couple without much vacation time or an older couple who want some mild adventures. However boats like Lake Sailor have done some remarkably adventurous things. Very few people know that all the way down the East Coast of the United States there are mostly protected and semi-protected waters. Further, a remarkable amount of the East Coast for one reason or another is still relatively lightly populated. This is difficult to believe if you travel the land bound highways but by water you can often be quite far from populous areas. If you start from Eastport, Maine there is a short stretch from Lubec to Cutler with a bold shore and no islands to get behind but even there you will find a few little creeks that a boat this size can get into. When you get down to New Jersey there is one 26 mile stretch with no protection where you'd have to pick your weather a bit. Other than this you are mostly pretty close to a way to get out of the weather most of the time all the way down to Key West, Florida. It would be a marvelous adventure to start south from Eastport, Maine at one end of the East Coast in, say mid-August, and work your way south, sailing only on good following wind days, and on bad weather or contrary wind days staying where you are and exploring. Pacing yourself in this manner you would be south of Cape Cod in time to still be warm in southern New England and south of Cape Hatteras before winter set in. The rest of the way south it never really gets cold enough to be a serious problem. The East Coast of the United States has an enormous number of creeks, rivers, islands, little hidden towns, etc. You could easily spend a lifetime exploring between Maine and Florida. In the late 1800s and into the early 1900s a number of people took little vessels just like Lake Sailor on long cruises like this and there is no reason not to do the same today. In a very real sense Lake Sailor is the ultimate little yacht. You can build bigger boats or fancier boats but everything you add to a boat beyond what you see in this design also takes something away through complication or restricted cruising grounds, etc. There is probably more pleasure for the dollar in boats like this than in any other size or style.

| Particulars | Metric | English |

| Length Over Rails | 4.076 meters | (13' 4-1/2") |

| Length on Waterline | 3.609 meters | (11' 10") |

| LWL (light) | 3.559 meters | (11'8") |

| Beam | 1.05 meters | (3' 5-5/16") |

| Waterline Beam | 1.019 meters | (3' 4-1/8") |

| Waterline Beam (light) | .986 meters | (3'2-13/16") |

| Draft (heavy) | .15 meter | (0'5-7/8") |

| Displacement (heavy) | .191 cu. meters | (6.75 cubic feet, with two average people aboard) |

| Displacement (light) | .119 cu. meters | (4.219 cubic feet, with one average person aboard) |

| Displacement (heavy) | 196 kilograms | (431.75 lbs.) |

| Displacement (light) | 122.47 kilograms | (270 lbs.) |

| Wetted Surface (heavy) | 3.066 sq. meters | (33 sq.ft.) |

| Wetted Surface (light) | 2.732 sq. meters | (29.41 sq.ft.) |

| Sail Area | 3.03 sq. meters | (32.6 sq.ft.) |

| Sail Area/Wetted Surface | 1.11 | |

| Center of Effort (CE) | 1.873 meters (forward of aftmost station) | |

| Center of Lateral Plane | 1.702 meters (without rudder) | |

| Lead | 4.7% | |

| Center of Buoyancy | 1.76,0,-.043 (X,Y,Z coordinates, heavy) | |

| Center of Buoyancy | 1.778,0,-.031 (Coordinates, light) | |

| Waterplane Area | 2.493 sq. meters | (26.837 sq.ft.) |

| Waterplane Area (light) | 2.264 meters | (7.428 sq.ft.) |

| CLP (w/o rudder) | 1.702 (X coordinate) |

Conversion Factors (for non-metric speakers)

1 meter = 3.281 feet

1 square meter = 10.765 sq.ft.

1 cubic meter = 35.32 sq.ft.

1 kilogram = .4536 lbs.

| Study Plans | $66 | |

| Complete Building Plans | $154 | |

Stock Plans Order Form / Back to Aruna 33 / Back to Design Page / On to Island Girl 24 / Stock Plans List